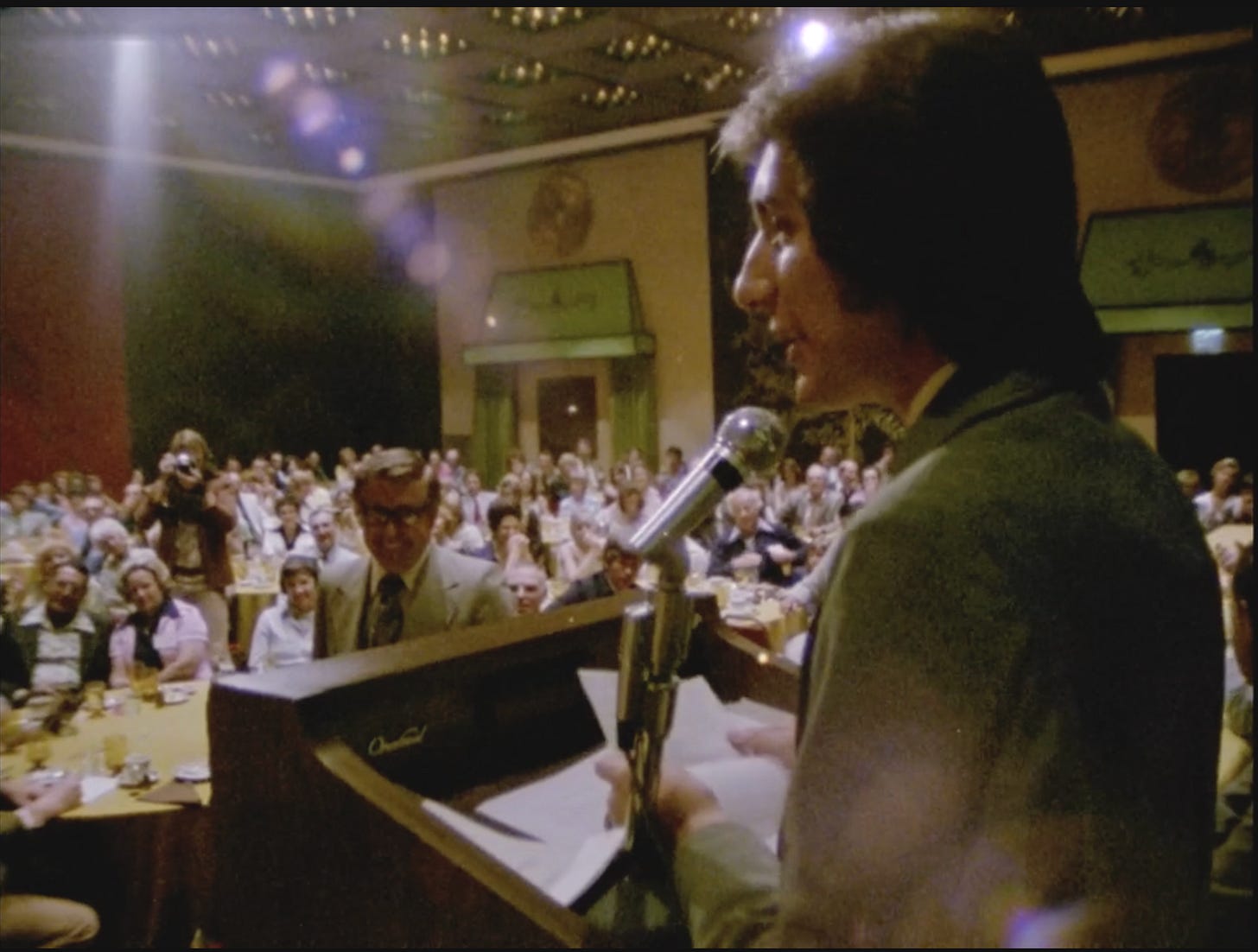

In the summer of 1976, Scott McKain, an aspiring professional speaker between his junior and senior years of college, was asked to emcee and give a speech at the awards banquet that would follow the World Livestock Auctioneer Championship.

This was in New Holland, Pennsylvania. “When I arrived, the person running the event told me these ‘crazy Germans’ were doing a documentary about the [championship],” Scott wrote me via email recently. “As we were doing the sound check for the program, that’s when I first met Werner.”

The email goes on:

Herzog and I hit it off — I think because what I was doing was fairly unique for German culture and I had always been fascinated by filmmaking and was totally interested in what he was doing. We ended up having a beer after the evening’s festivities. I honestly had no idea who he was — even though he had already directed his early classics.

Scott first reached out to me a few months ago when he subscribed to this here Werner Herzblog, letting me know that my posts, while of little interest to most people, were of particular interest to him, because he’d been in two of Werner Herzog’s films.

Even a simple Google search on the company’s functionally obliterated platform reveals that Scott McKain played the bank representative in 1977’s Stroszek. Smartly dressed and loquacious, the rep visits Bruno (Bruno S.) and Eva (Eva Mattes) at their mobile home to discuss repossession, his warm and polished manner both a harsh juxtaposition of the terrible information he’s delivering—that they’ve fallen so behind on payments that the bank may soon intervene—and an anchoring, if quietly villainous, presence for these two souls lost in America.

The other Herzog film in which Scott appeared is that documentary those “crazy Germans” filmed in the summer of 1976—How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck, subtitled “Observations on a New Language.”

From A Guide for the Perplexed, Herzog explains:

I was fascinated by livestock auctioneers and had the feeling that their incredibly fast speech was the true poetry of capitalism. …there is something final and absolute about how auctioneers speak. How much further can it go?

Herzog, who narrates the film in German, admits as much toward the end of How Much Wood Would’s short 45 minutes:

What frightens me personally is the idea that our system has managed to produce a language that almost surpasses the boundaries of extremity… Sometimes I ask myself, ‘...and how did our economic system spawn this language?’

Still, Herzog isn’t resolutely apocalyptic about the prospects of this new language. He’s scared but also in awe of its beauty, drawn to how “there is real music in their delivery, the sense of rhythm these people have.” In the film, contestants of the championship describe how they practice their auctioneering, often utilizing the repetitive movements of chores, like milking cows, or the copy-pasted nature of driving vastly stretching Texas highways, pointing to telephone polls as if they’re rapidly betting ranchmen. Like speaking a new language, they’ve sung it over and over, regardless of who was listening.

What language do auctioneers speak to themselves?

How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck is ostensibly straightforward, bereft of strange detours and narrated as literally as Herzog’s most utilitarian works. Of 52 contestants, Herzog and his camera crew film an impressive bulk, including the winner (Steve Liptay), second place finisher (Ralph Wade, he of the practiced milking), and the first woman to ever compete in the competition, whose name goes unmentioned, though Herzog does go out of his way to make other voiceover comments like, “This is Ralph Wade from Miami in Oklahoma. He came in second.”

From a teenage competitor to an old timer who doesn’t seem to be really trying, the accumulation of so much melody over the course of the film gains power once you’ve left the slipstream—once you can step back and see the herd for the hooves. And even though How Much Wood Would begins with Steve Liptay explaining the basics of auctioneering speech, there is so much variation and so many instinctual subtleties that their language is still largely incomprehensible. In A Guide for the Perplexed, Herzog confirms the difficulty in translating:

The jury of the competition was judging how wildly the auctioneers could accelerate their speech, but this was also a real auction, and at all times the auctioneers had to look carefully into the crowd for bidders. That might sound easy [ed: no, it really doesn’t], but the buyers were competing amongst themselves. No one wanted anyone—except the auctioneer—to know they were bidding, so their gestures were miniscule, perhaps just a flick of a finger or a quick blink of an eye, and had to be recognised instantly in a sea of three hundred people.

This Herzog only complicates further by layering his German translation over the voices of English speakers, which often stifles the voices on screen, allowing only small snippets of their voices to emerge beneath Herzog’s. If you don’t speak German, you need subtitles, which translate Herzog’s German and not the English Herzog was originally translating, further abrading the nuance of the language first spoken.

When Herzog and his crew encounter Pennsylvanian Amish families who have come out to the auction, he emphasizes how different their German dialect—originating in the Palatinate region—is from his own, to the extent they must use English to bridge some gaps. When the Amish Herzog interviews do not have a phrase for “world championship,” Herzog’s voice glows with a bit of fascinated admiration. He says in voiceover:

Their most remarkable trait is their puritanical attitude towards developments in our society. The Amish reject the ideas of capitalism and competition. So they are the very antithesis of the world championships that are being held in their region this year.

Translations within translations butting against translations—it’s flummoxing at times, but still a sign of how lovely language can be even when it’s not fulfilling its purpose. “Sometimes I think that this here could be the last remaining lyrical form,” Herzog says in his native tongue. It’s seductive to agree with him, given how hypnotic and even soothing scene after scene of competing auctioneers becomes.

But “the person running the event” in Scott McKain’s email to me was wrong about one thing: those “crazy Germans” actually included one American, Ed Lachman.

This is the guy who’d go on to shoot True Stories, Desperately Seeking Susan, Mississippi Masala, Light Sleeper, The Limey, Carol, The Virgin Suicides, and this year’s Maria with Pablo Larrain. He credits Herzog as a key person in his filmmaking genesis, one of three camera operators on How Much Wood Would along with Herzog mainstay Thomas Mauch and Francisco Joán (who was an operator on The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner).

From an interview with Lachman in the ’90s by Vincent LoBrutto:

While in art school in France, I met Werner Herzog at the Berlin Film Festival. He really gave me my first start by working on documentaries, La Soufriere, How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck, and Huie’s Sermon. That led to working with Wim Wenders on Lightning Over Water and Tokyo-Ga, then with Fassbinder on Blue Train, and then Voker Schlondorff on A Gathering of Old Men. I think I was the only cameraman who worked with all the formidable directors who came out of Germany in the seventies. Their visual styles emanated from a philosophical and a political context.

He goes on, coincidentally speaking to the concern at the heart of this, his first documentary: “I learned through each director’s perspective that one could find their own language to tell stories.”

Maybe it’s a bit of a stretch to see Lachman’s primordial work here and think about True Stories, but the way talking head (heh) interviews are shot in David Byrne’s film, framed like dispatches from rich and broader lives, stylized to be both documentarian and surreal, feels prominent here. Each auctioneer in How Much Wood Would is treated similarly while competing, like a talking head communicating in a new and unfamiliar language, and each head or face captured with care and curiosity.

Later in the interview with Labrutto, Lachman speaks Herzogian:

All films are really in a sense documentaries. Everything comes together for that one moment, happens in that one moment, and cannot be reproduced. No performance is exactly the same. The movement of the camera, the light, how actors hit their mark isn’t exactly the same as in a former take. The director and the cameraman are really the first audience…

Haha, hell yeah. I love that shit.

At the end of How Much Wood Would a Woodchuck Chuck, Scott McKain hosts the awards banquet for the championship. Winner Steve Liptay, beatific look on his very Midwestern face, gets up to speak. “I can’t think of any profession…where they hold such a contest where they just get the best all together and choose the winner,” he states, Scott just behind him, and immediately one wonders if that’s true. It can’t be. Because it’s not. But that Steve Liptay thinks so speaks to the effectiveness of the auctioneer’s language, and how well Herzog, and likely everyone at the championship, assumed it would survive.

It hasn’t, at least in a form that won’t eventually go obsolete soon enough, because mass-market animal processing will devour the earth and all language with it, but also because: do cattle auctions even exist anymore? This championship still does, at least. But beyond that ceremony? The economic viability around them has likely died—so then wouldn’t the vitality of the language follow soon enough?

Mostly I’m fascinated with Scott’s experience with Herzog, at least as he tells it to me. It’s such a contrast to Maarten t’Hart’s account of Herzog on set in eastern Europe for Nosferatu, or Herzog in the jungle in Burden of Dreams, shepherding Fitzcarraldo—in Scott’s stories, he is so much more affable and curious than domineering and haunted.

Maybe the stress of making those films transformed him a bit, or maybe some of the people he met in America—those who shared their hopes for that they could take part in the American dream, however facile and ultimately false that promise turned out to be—kept his spirits up. I can’t say.

Sources:

Herzog, Werner, and Paul Cronin. Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed. London, Faber & Faber, 2014.

LaBrutto, Vincent. Principal Photography: Interviews with Feature Film Cinematographers. Westport, Praeger Publishers, 1999. pp 119-133.

McKain, S. Email to Dom Sinacola. 19 October 2024.

McKain, S. Email to Dom Sinacola. 2 January 2025.