Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970)

"Not knowing what to do, the animal defecated in despair, something that looks exquisite on screen."

Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus edited the majority of Werner Herzog’s early-career features, totaling 20 films—up to her last with him, 1984’s Where the Green Ants Dream—all of which, according to Herzog, she openly hated. Likely, she still does. About a year ago, when Herzog was a guest at Princeton’s Visual Arts Program for a showing of Grizzly Man, he spoke of Mainka-Jellinghaus in the manner he normally speaks of her, which means he talked about how bad she thought his movies were.

“She disliked the end product of all of my films… she refused to show up to every single premiere, every single opening night, of my movies. Every single one. She said, ‘This is so bad, I do not want to show up, I feel embarrassed.’

“And you know the only film where she showed up, there was only one [here it’s important to note that Herzog leans in for emphasis, holding up his pointer finger], one single film, where she said, ‘This is a truly great film.’ Even Dwarfs Started Small.”

Maybe anticipating the silence that would follow such a revelation, Herzog quickly continues, “And I think it’s Harmony Korine’s most favorite film. One of David Lynch’s favorite films. Even Dwarfs Started Small. So…”

No one says anything, so the original audience member just squeaks out a “thank you.” Herzog goes on to provide additional context, that he brought that all up to illustrate how he never works with “yes men or yes women,” but it’s still the distaste that lingers in his stories, how such a close collaborator thought he sucked shit. Likely still does.

As far as Harmony Korine is concerned, at least Herzog knows for sure that Even Dwarfs Started Small is the younger director’s favorite movie, because Korine says as much in the foreword to A Guide for the Perplexed:

the first time i saw even dwarfs started small i knew i wanted to make films. i had only experienced this once before, when as a boy i watched a w.c. fields movie marathon next to a man dying of emphysema. i could not imagine what type of human being could come up with such insane ideas. i could not understand how these dwarfs could laugh so intensely throughout the film. after getting to know the great man it is obvious where he gets his ideas. he gets them from a deep place where formal logic and academic thinking need not exist.

You can see Werner Herzog’s ecstatically primordial nature in the genetics of Korine’s films. (You can literally see Herzog in Julien Donkey Boy.) Korine seems to get his ideas from “a deep place” too. Herzog might call that sleeping.

From Vincent Canby’s September 1970 review of Even Dwarfs Started Small, in the New York Times:

At a press conference following the screening of his film earlier in the week, Herzog, quite correctly, declined to explain the film and turned aside suggestions of any relationship to the more calculated, surreal work of Buñuel. His film, he said, came on him "like a nightmare."

Canby had less exceptional feelings about the film than Harmony Korine, or David Lynch supposedly, or Beate Mainka-Jellinghaus:

Herzog is a highly skilled director, but his images, because of their essential meaninglessness, become their own reason for being. "Even Dwarfs Started Small" eventually is indistinguishable from its Germanic, side-show spectacle, as if it were a movie that had been conceived by the same kind of perverse, uninvolved intelligence that had created the world of the film.

More than 60 years later, “perverse” bears a lot of weight for a critic to lob so casually, and the assumption that Herzog’s images are meaningless only because he (“quite correctly”) refuses to explain them doesn’t really line up with saying “Herzog is a highly skilled director” in the same sentence, but also: who cares.

The reality is that following Signs of Life, he received government money to make more movies, so he wrote the script to Even Dwarfs Started Small in a week and went straight into filming. He had no time for a formal film school education; he claims he didn’t even know movies existed until he was 11, born literally during the war and raised in a remote Bavarian village when his mother escaped the bombings in Munich. If his films are uniquely oneiric, it’s because they have no influence, no precedent. They come from somewhere else.

Originally recorded for the 1999 Anchor Bay DVD of Even Dwarfs Started Small, a commentary between Herzog, Crispin Glover, and curator/Anchor Bay co-founder Norm Hill (who’d eventually go on to produce Herzog’s The Wild Blue Yonder) gives Herzog room to remember how he “was really into nightmares at that time,” as one might think back on collecting pogs or reading about dinosaurs.

Having filmed throughout the Sahara for what would become Fata Morgana (1971), Herzog and a small crew of eight or nine gathered with their cast of dwarfs on Lanzarote, the volcano-scarred, easternmost Canary island, for “4 to 5 weeks of shooting” Even Dwarfs Started Small. Following that, Herzog and cinematographer Thomas Mauch would go on to the other side of the continent to make The Flying Doctors of East Africa (1969), which incorporates images from the Fata Morgana footage. “There were three films almost intertwined, interwoven,” Herzog says early in the commentary. “For me it’s almost like one film.”

Herzog says shit like that constantly, not lying but not attempting to coddle anyone who may be stymied by the fact that the three movies aren’t alike at all. In the same way, he returns to a line he uses a lot, including in this commentary, that he considers Fitzcarraldo his “best documentary.” Frustrating to parse, maybe, if you’re looking for a clear answer or you lean into functional semantics—how is it a documentary in any common understanding of the medium?—like any person confronting our ceaseless access to everything. Watching Werner Herzog’s films can feel like negotiating literality, admitting that truth can transcend whether something happened or not, but also remembering that he does not tread in irony, so that when he says he only rarely dreams, he means that quantifiably: “Maybe once or twice a year.” It’s like holding two contradictory ideas in your head, the first that a manipulated reality can still reflect what happened, can still be a conduit to truth’s emotional contours and shared experience, and the second that images can be ostensibly meaningless but still vibrate with latent power. Perhaps he makes films to compensate for the lifelong dearth of dreaming. This stuff doesn’t conform well to straightforward explanations.

Even Dwarfs Started Small is about an institution that rests upon an alien landscape (“lunar,” Herzog calls it), the closest town 40 miles away, “Dolores Hidalgo” as indicated by a sign outside the institution’s grounds. Though stuck in the soil of Lanzarote, the sign points to a Mexican city in the state of Guanajuato. Though large and intended for numerous people living together, the institution is sparsely populated by little people. A little person runs the institution too. Later, a passerby heading to Dolores Hidalgo stops to ask for directions. She’s a little person. The word “dwarf” is never mentioned, though the spaces the characters inhabit aren’t meant for them. Beds are too high, chairs too tall, door handles out of reach and nudie magazines depicting the lithe, 5-foot-plus bodies of women feel beamed from another civilization. Though they are the only people in this world, this world is not theirs.

Herzog takes a moment in the film’s first 5 minutes to show us an aerial photograph of the isolated site, labeled in Spanish, but the image has little further bearing on the events to come. Geography hardly matters here, the photo a detail with no narrative purpose frustrating the nature of this world—grounding us in a specific but unfamiliar reality, tapping into a deep place dug out by tidal forces in our brains. Because from there, the institution slips into chaos as the patients rebel against the director (Paul Glauer), who’s desperately holed up in his (disproportionate) office with Pepe (Gerd Gickel), the only patient he managed to subdue, tied to a (disproportionate) office chair. Outside, a motley crew of little people gleefully destroys everything they can in the compound, first throwing rocks and harassing blind guards Azucar (Erna Gschwendtner) and Chicklets (Hertel Minkner), then inevitably watering flowers with gasoline, murdering a pig, mounting a mock Catholic procession with a monkey tied to a crucifix, beating the shit out of Chicklets, potentially killing Azucar, and pushing a car into a volcanic sinkhole, a spaghetti dinner absolutely ruined and the smallest of the little people, Hombre (Helmut Doring), cackling to death. Why are the guards blind? Inside, Pepe can’t stop laughing. Chickens, animals Herzog has already established as avatars for primordial stupidity in only his second fiction feature, cannibalize a one-legged peer. Entropy takes over, so that even the director snaps, running away to yell at a leafless tree, unnoticed. A dromedary seems terrified when it can’t decide between getting up or lying down forever. In the commentary, Herzog describes how the trainer was just outside frame, giving contradictory orders to the animal. Unsure what to do, the dromedary shits, turds tumbling out of its confused anus. This causes Hombre to laugh harder, because the only thing funnier than anarchy is a camel getting scared and shitting itself. So hard he coughs uncontrollably, his soul barking from his body, the camel one more creature hilariously evacuating itself with nothing else to do at the end of the world.

From A Guide for the Perplexed:

...the creature was a docile and well-trained animal whose owner was standing two feet outside the frame giving orders. he was trying to confuse the dromedary by constantly giving it conflicting orders by hand: sit down, stand up, stand still. Not knowing what to do, the animal defecated in despair, something that looks exquisite on screen.

Something that looks exquisite on screen. Be still my heart.

“I saw the whole film like a continuous nightmare in front of my eyes, and I wrote it down very quickly,” Herzog says during the commentary. “Right after [filming in the Sahara] I started shooting Even Dwarfs Started Small, and much of the climate of the film, much of the gloom of the film was somehow triggered by events that happened in Fata Morgana.” Enduring extreme weather and extreme thirst, malaria and parasite infection, imprisonment in Cameroon—Herzog left the desert glistening with near-death dread. “[Even Dwarfs Started Small] has such a profound despair in it, it has such a nightmarish quality to it that I think it will survive even more average films like Aguirre, the Wrath of God, which looks like kindergarten compared to this here.”

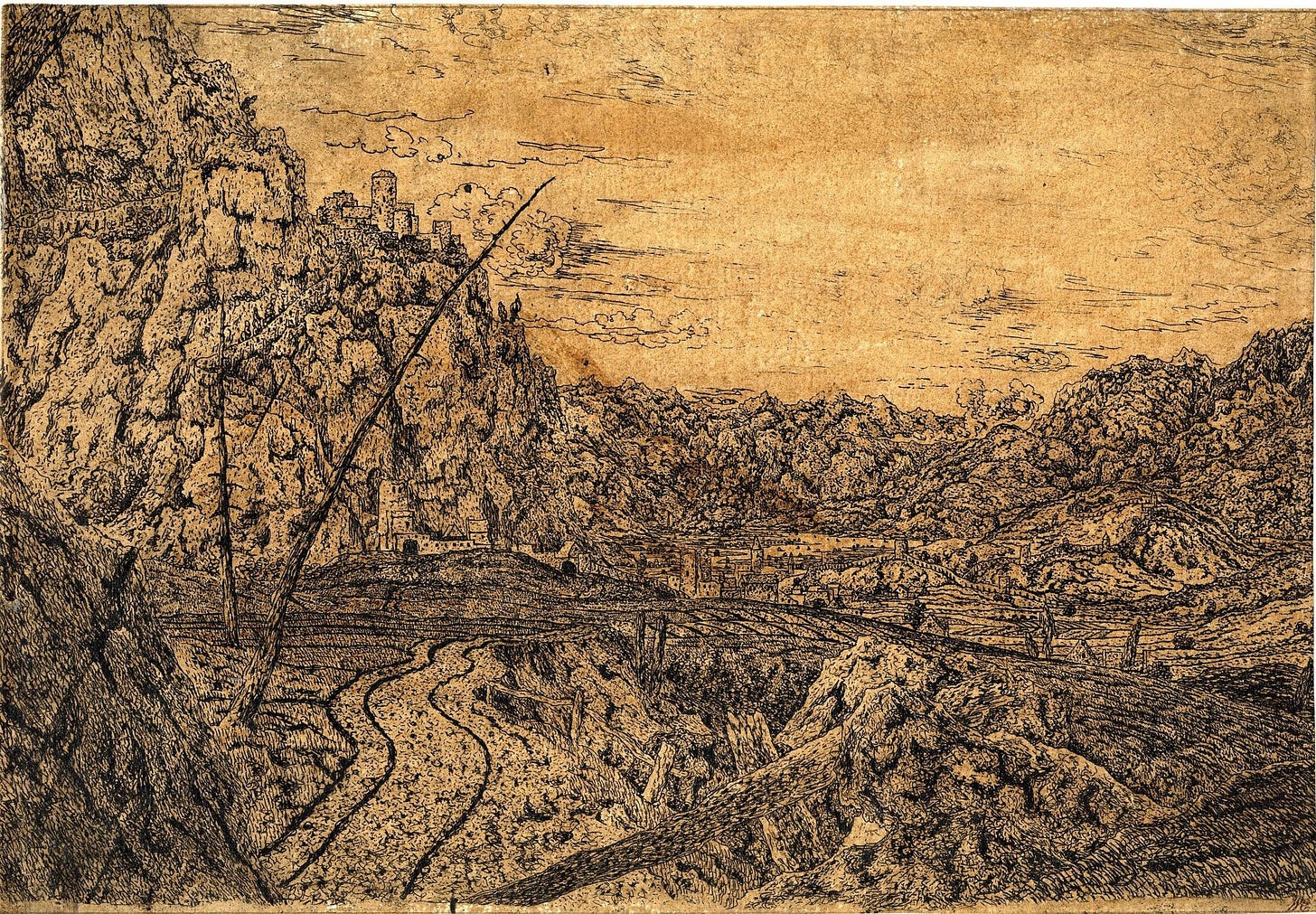

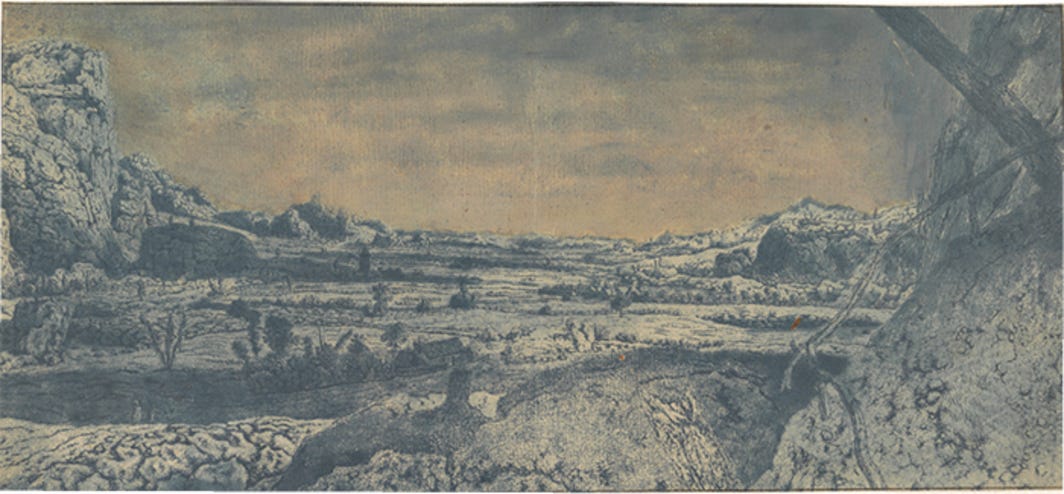

Shot with a “relatively wide-angle” 24mm lens by Thomas Mauch (“because,” as Herzog states in Guide for the Perplexed, “I wanted the characters to be in focus amidst the extraordinary landscapes”), the film’s stark black and white accentuates the harrowing events breaking out on screen. Subconscious horror manifests in careful sound design. Wide shots of the desolate compound shift to erratic handheld blurs, attempting to capture all of the ensuing mania. “The whole film is about something ecstatic, something wild,” Herzog says on the commentary. “Like in our wildest nightmares. Something that is beyond our average experience.” He alludes to the intricate landscapes of 17th century Dutch artist Hercules Seghers, to their cosmic and barren scale.

“Mountain Valley with Fenced Fields” by Hercules Seghers

From A Guide for the Perplexed:

The dwarfs in the film aren’t freaks; these are well-proportioned and beautiful midgets. …If the film has a ‘message’ it’s that we and the society we have constructed for ourselves—with oppressive and institutionalized violence, rules and regulations—are monstrous, not the dwarfs. We all have something dwarfish, inadequate, impotent and insignificant inside us, as if there is an essence or concentrated form of each of us screaming to escape, a perfectly formed representation of who we are. A very real nightmare for some people is knowing that deep down they are a dwarf.

Herzog’s ignorance glows gratuitously here—and as much as he loved making Even Dwarfs Started Small, everything he says about the film feels slightly condescending when it’s not overtly so (e.g., “when you find one midget you find several, so for a year I went from one to the next, hiring everyone”)—but he’s speaking to a terror that’s consumed me lately. I laugh at Hombre unable to get onto a bed because the bed doesn’t accommodate his size, and I laugh because he puts down magazines, each one no thicker than half an inch, to boost himself up, but laughing betrays the bleak-empty sensation of looking to the future and seeing nothing but helplessness waiting for me. My grandmother had Parkinson’s and sometimes I catch my hands twitching without knowing it. I’m afraid, deep down, I’m waiting to lose control of myself.

“A Mountain Valley with Dead Pine Trees” by Hercules Seghers

I don’t find Herzog’s gaze exploitative. Instead, we’re always placed at eye level with each little person in frame, the objects and environment around them growing outsized and grotesque. When Crispin Glover, seemingly fulfilling his role as cinema’s unnerving milquetoast, quietly asks Herzog about the music that begins the film, Herzog recalls recording a young girl singing a “folk song” in a cave on the island, and not being particularly pleased with her performance. As he also details in A Guide for the Perplexed, he then encouraged her to “...‘[s]ing until [her] soul departs.’” “I said. ‘Sing your lungs out of your body.’” The result is something transportive.

Herzog may have been into nightmares in his mid-20s, but his career would go on to demonstrate an obsession with dreams. Maybe because dreaming is so exceptional for him, but his protagonists are always dreamers, people who must pay for pushing at the borders of acceptable reality: Fitzcarraldo pushing a boat over a mountain, Aguirre pushing a dying army toward an imaginary city, Dieter Dengler pushing his body to the edge of gravity. Herzog tells Paul Cronin, “I can sense the hypnotic qualities of things that to everyone else look unobtrusive, then excavate and articulate these collective dreams with some clarity.” Dreaming Herzog describes as flight, as escape, as the closest we can get to singing ourselves from our bodies. There’s nothing more frightening, then, than to be trapped in one.

From A Guide for the Perplexed:

Destroying everything they can find and turning everything upside down has been a truly memorable day for the midgets; you can see the joy in their faces. Audiences walk out aching from laughter.

Following WWII, the German government required rigorous censorship for films to be released in theaters. Knowing he’d have his film banned—what with all its blasphemy and anarchic tendencies—he opted to self-distribute Even Dwarfs Started Small in 1970, still facing protests and death threats wherever he took it. From all angles at that: from revolutionaries who claimed he was portraying the civil rebellion of the late ’60s as violent and wrongheaded, from animal rights activists decrying scenes of animal mistreatment, and from white supremacists because…I’m not entirely sure why, to be honest. Herzog finds the actions of the little people justified as they rage against an oppressive society, and swears the monkey wasn’t harmed, nor that his crew killed the pig, because a butcher was killing the pig anyway, but that he does have trouble watching the scene in which piglets suckle at the dead pig’s teats, not to mention the scene toward the end of the film where the institution’s director loses his mind in a shower of glass and freaked out chickens. In the midst of the detritus, I can’t help but catch a glimpse of a chicken gone totally immobile.

The most well-known anecdote to come out of Even Dwarfs Started Small is about how the man playing Territory, Gerhard Marz, burst into flame when attempting to water the flowers with gas, which was not too long after the car they eventually sent plummeting down the sinkhole completely ran over him. Miraculously, Marz was fine in both cases, but as part of a deal with the crew, Herzog vowed to launch himself into a nearby cactus patch if shooting completed without any further injuries. It did, so he did too, a spectacle of masochism as an act of solidarity.

Watching Even Dwarfs Started Small with Herzog talking along, maybe I’m just grasping at anything, but I get the sense that this is painful or him to watch. Not only because he was coming out of the desert a traumatized man when he made it, nor because it’s arguably his bleakest—or at least his most anxiety-inducing—film. It’s because of the responsibility he feels for all of the accusations and controversies levied at his work, beholden to them even if he doesn’t have to agree with them. He accepts them. Same goes for watching the scenes with Hombre, Herzog musing that he had to restrain himself from yelling, “cut,” even as his concern for the actor grew with every diaphragm-destroying cough. “This is hard to watch,” he mentions, seemingly to no one.

But he still does. There’s purpose to these images. “It reduces the horror, banishes it, pushes it to a safe place. And the pain hopefully is over and the nightmare hopefully is over.”

Sources:

Canby, Vincent (1970, September 7). ‘Dwarfs Started Small.’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/17/archives/dwarfs-started-small.html

Glover, Crispin and Werner Herzog and Norm Hill. Audio commentary. Even Dwarfs Started Small. Dir. Herzog. Shout Factory, 2014. Blu-ray.

Herzog, Werner and Paul Cronin. Werner Herzog : A Guide for the Perplexed. London, Faber & Faber, 2014.

Friedrich, S. (2023, March 27). Werner Herzog talks about Beate Mainke-Jellinghaus 4-6-22. Vimeo. https://www.vimeo.com/732773941